IQA before Deep Learning - The Feature Engineering Days

Back in 2016/2017, I was working on my first major Machine Learning project: my Master’s thesis.

I consider this work as my initiation into AI/ML and the first milestone of a long journey that has now lasted around 10 years.

Ten years in computer science is like a geological era, but sometimes it’s worth—and inspiring—to look back.

This is part of the introduction I wrote in 2016:

“Back to 2010 the number of photos taken worldwide was 0.35 trillion. 60% of them were captured with a specialized camera device and the remaining 40% with smartphones or tablets. Almost seven years later the trend has been inverted and the role of mobile devices in digital photos is leading. In 2017 the number of photographs taken worldwide is expected to reach 1.3 trillion and 80% of them will be acquired with mobile devices. This shift is driven by mobile social network applications which provide the ability to upload and share photos over the Internet. It is enough to think that the daily number of photos shared through social applications such as Facebook, WhatsApp and Snapchat is almost 3 billion.”

The research topic

Image Quality Assessment (IQA) is a branch of computer vision focused on developing algorithms that estimate the quality of digital images as perceived by humans.

Why quality of digital images needs to be evaluated?

The interest in evaluating quality comes from increasing demand of digital contents. This leads digital media providers like e.g. Meta (just to cite one) to find ways to increase the quality of services.

What affects the quality of an image?

Today’s answer - with the diffusion of Generative AI - is probably different with respect to 10 years ago, when mobile device cameras weren’t so good. Indeed, the main focus of my thesis was the quality degradation introduced throughout the digital image processing pipeline — from sensor acquisition, to transmission over digital channels, to storage.

Let’s look at some examples of degradation, also referred to as artifacts (or noise):

- saving digital images as JPEG - the most diffused file format - introduces a blocking artifact. It is worth noting that this file format is always used in mobile devices.

- a subject in motion can be captured with blurred artifacts due to optical system limitations

- few but very noisy pixels can occur during transmission on a digital channel, the so called salt-and-pepper noise

- white noise is also widely used as representative model along the pipeline, it is sampled from a gaussian distribution

- ringing distortion can be caused by high compression rates in the JPEG and JPEG2000 algorithms. It is mostly caused by truncation of high frequency components in the frequency space and occur in proximity of sharp image edges.

- fast fading artifact can occur e.g. as sensor-level noise due to rapid change in illumination (high speed imaging)

A picture is worth a thousand words.

There are three main families of IQA algorithms:

- full-reference: the reference image is available

- reduce-reference: partial information of the reference image are available

- no-reference: as the name suggests, the reference is missing.

Ten years ago, no-reference was the hottest topic, and it probably still is today.

Algorithms and practice

The work was developed around two quite famous algorithms for that time: BRISQUE 1 and BLIINDS-2 2.

We started by studying two versions of the BRISQUE algorighm provided by the authors. The first one was in C++ while the second in Matlab. BRISQUE is characterized by 18 hand-crafted features in the spatial domain, they are computed on the original image and a rescaled version (factor of 2), for a total of 36 features. We discovered that the features computed on the rescaled version are quite different in value between Matlab and C++ implementations. Further investigation revealed that this discrepancy stems from the sensitivity of the features to resampling methods that rely on filtering techniques (e.g., bilinear, bicubic).

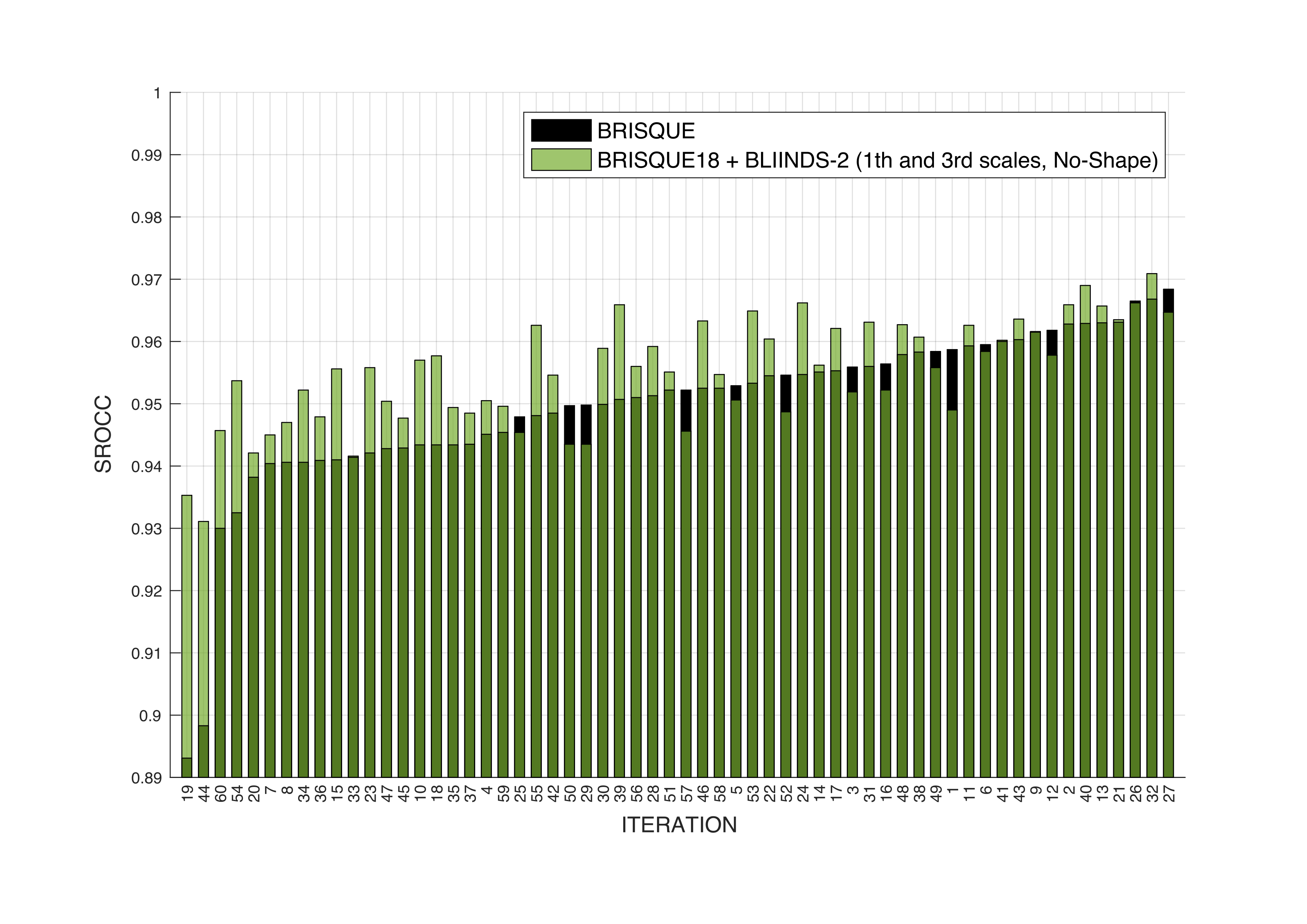

An ablation study was carried out to quantify the influence of the last 18 features to the Spearman’s Rank Order Correlation Coefficient (SROCC). This metric is used to measure the correlation between human ratings and the model’s predicted quality scores.

The results show that the first 18 features yield an SROCC of 0.9327, while using all 36 features increases the SROCC only to 0.9522. In short, the additional features provide minimal benefit. The algorithmic choice was then to replace these 18 weak features with something else: features from BLIINDS-2. This algorithm works in the frequency domain, so we merged features from both spatial and frequency domains. Wonderful AI when models are ensemble!

Image 2 shows the comparison between the performance of BRISQUE (default version) versus our new ensemble model computed on the LIVE IQA dataset 3. Training and test splits were generated using fixed seeds to ensure fair comparison. We can appreciate an overall improvement with respect to the baseline!

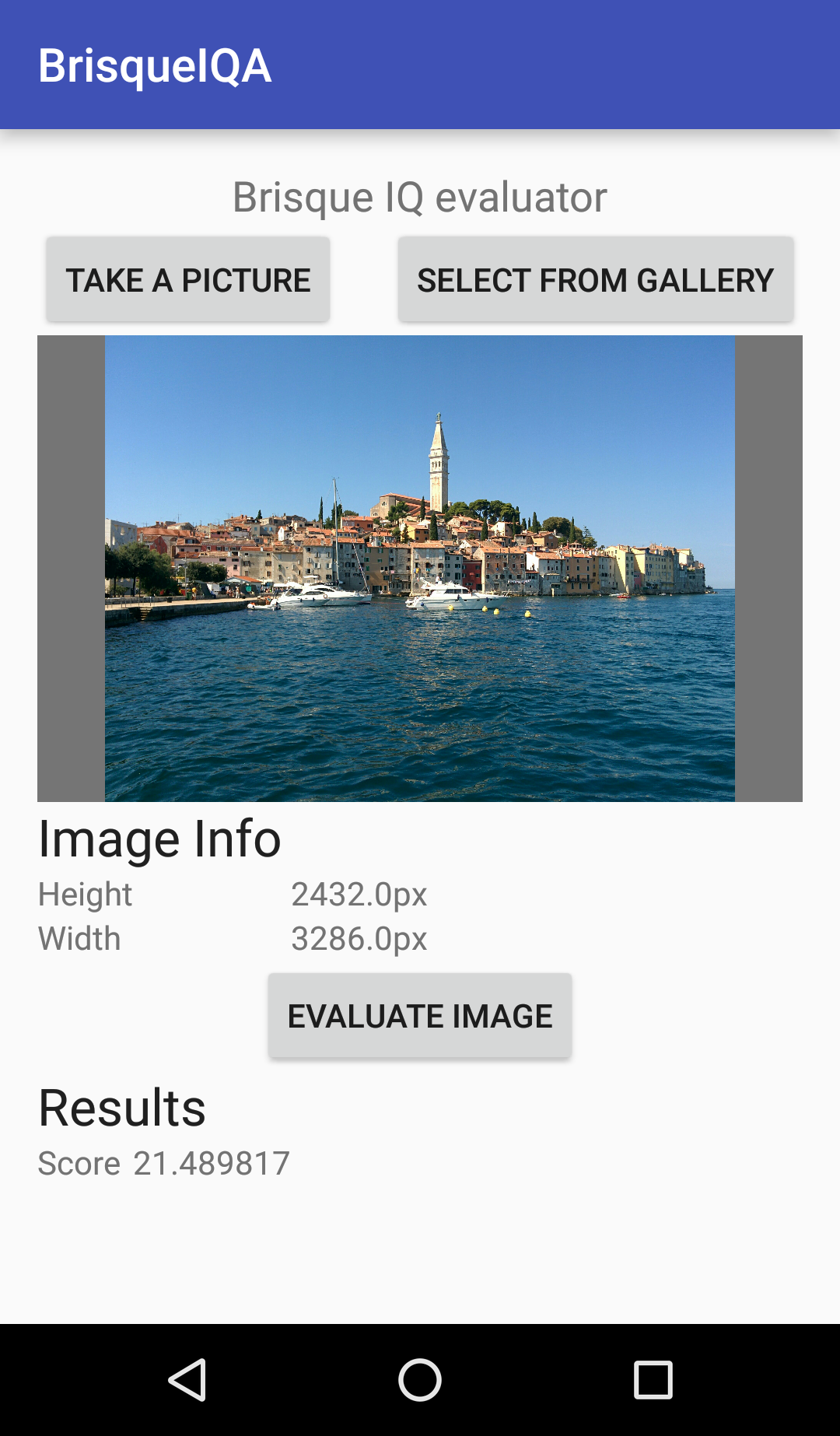

One of the goals of the thesis was to develop a fast and efficient algorithm for deployment on limited-resources mobile devices. A huge amount of work have been made to improve the C++ implementations of BRISQUE and BLIINDS-2. An Android app was crafted with models and algorithms integrated by using Native Development Kit (NDK). Unfortunately at that time the GPU support wasn’t good enough to be used. Image 3 shows a screenshot of the Android app implementing the IQA algorithm.

Conclusions

Back in 2016, the first research applications of Deep Learning to IQA were emerging. From an educational perspective, my advisor felt it was important for me to first understand hand-crafted Machine Learning before moving into Deep Learning. In hindsight, I think that seemingly counterintuitive choice was the right one. Just a year later, I won a grant for a Deep Learning project with the same supervisor.

Fast forward to 2025, and the number of photographs taken worldwide is estimated to reach approximately 2.1 trillion per year, highlighting the ever-growing importance of efficient image quality assessment. Even today, I continue to make use of hand-crafted feature–based ML algorithms, as they remain valuable tools alongside modern Deep Learning approaches.

You can find the full thesis here.

If I didn't quote you or if you want to reach out feel free to contact me.

© [Simone Brazzo] - Licensed under CC BY 4.0 with the following additional restriction: this content can be only used to train open-source AI models, where training data, models weights, architectures and training procedures are publicly available.

-

A. Mittal, A. K. Moorthy and A. C. Bovik, “No-Reference Image Quality Assessment in the Spatial Domain,” in IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 21, no. 12, pp. 4695-4708, Dec. 2012, doi: 10.1109/TIP.2012.2214050. ↩

-

M. A. Saad, A. C. Bovik and C. Charrier, “Blind Image Quality Assessment: A Natural Scene Statistics Approach in the DCT Domain,” in IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 21, no. 8, pp. 3339-3352, Aug. 2012, doi: 10.1109/TIP.2012.2191563. ↩

-

L. Cormack H.R. Sheikh Z.Wang and A.C. Bovik. LIVE Image Quality Assessment Database Release 2. http://live.ece.utexas.edu/ research/quality. ↩